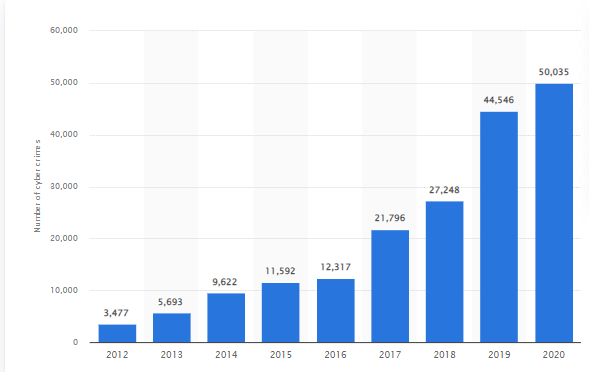

Last year, more than 50 thousand cyber-crime incidents were registered in India, with estimates suggesting over $ 20 billion losses suffered by consumers in the country due to cyber crimes

Despite the promise of cutting-edge growth and possibility brought to the table by an ever expanding cyberspace, there is little room left for the users to feel safe about the information they share- and many a time- information they don’t share.

Before we dive into the world of cyber safety (or the lack thereof), it is essential to recognise that we don’t quite feel safe about the information we choose to share outside the digital space either. Much of our vulnerability is at stake, and if we look at this conversation from a gendered lens, the stakes rise phenomenally. The dynamics of this phenomenon take on a much more amplified tone in the digital world, with the threat of data breaches forever looming in our internet-interactions.

A 2015 study revealed that nearly 20% of American women have been affected by cyber harassment. The internet mirrors its many physical counterparts in the sense that it is not the free space for human expression it claims to be, and it rather systemically contributes to this anomaly.

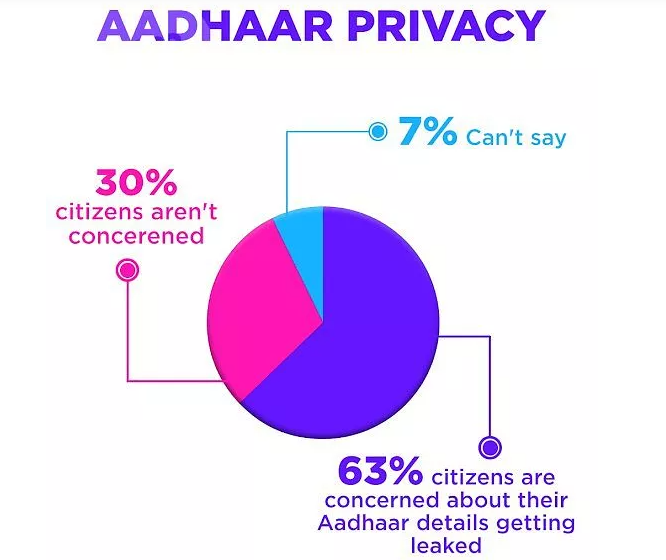

In 2018, it was public news that the world’s largest biometric database was up for sale, online. This was linked to none other than the information of Aadhaar-card holders, a mandatory identity card associated with a state-owned utility company. The type of information exposed was as sensitive as the holders’ fingerprints, photographs, retina scans, and so on.

Since then, the news has been stacked with breach upon breach that exposes the failure of the very systems meant to protect our data. Other than the crucial, fundamental questions we ought to be asking about how these systems profit from owning and sharing our data, it is equally imperative that we ask: What are the Psychological Implications of a Data Breach, or Even its Possibility?

“The psychological effects of cyberattacks may even rival those of traditional terrorism.”

–Dr. Maria Bada, Cybercrime Centre, Computer Laboratory, University of Cambridge, UK

The thought of the leakage of information sensitive to us, by someone we know, at even a small neighbourhood dinner, seems like the stuff of nightmares. To think that this can happen on a much larger scale, by an untraceable criminal, and can travel back to us in more ways than one, is a thought that sends shivers down the spine of many internet users today.

Credits: Statista

Disrupted sleep, sudden loss or increase of appetite, an increased vulnerability to turn to substance-use are just some of the most commonly occurring effects of data theft.

“With every exposure you have to it, with every reminder, you get retraumatized,” says Stanford University Psychiatry Professor, Elias Aboujaoude.

“You only care about your right to privacy if you have something to hide.”This is an everyday conversation-closer as per self-proclaimed middle-aged experts. But unfortunately, it seems to have find some legal validation too. The new Draft IT Rules 2021 recommends going to the extent of dissolving end-to-end encryptions on our everyday texts for not just the sake of ‘national security’, but also to grant legal immunity to the platforms used for these exchanges (WhatsApp, Instagram, for instance).

State-sanctioned surveillance, howsoever well intentioned, is not safe from the reach of hackers and cyber criminals. The argument against surveillance, according to Ronald Deibert, Director of The Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto, is simple: it is a preventive measure that could penetrate deeper than it can manage, and is at the risk of invading the privacy and threatening the freedom of speech of its victims.

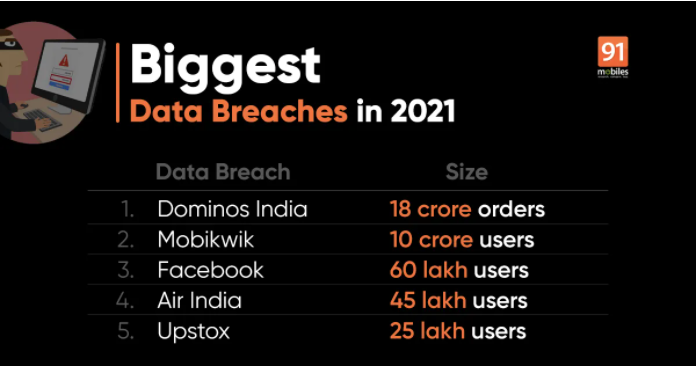

Credits: 91 Mobiles

What Can We Do About it?

Our perception of a threat and that of our ability to tackle it (better known as self-efficacy) shapes how well we are prepared for it. A study in 2012 specified that our perception of our own susceptibility to the threat and the cost and efficacy of the preventive and mitigative steps undertaken also contribute to how we react to a possible data breach or cyberattack.

Now, a lack of control over a situation that is perceived as dangerous could lead us to feel distressed and could affect how we engage with the online space altogether. This is where our Locus of Control comes into the picture, noted Ajzen in 2002. People who attribute most events in their lives to external forces such as fate, or authority figures, are less likely to practice safeguarding their data. A study by Bada & Nurse in 2020 ponders whether the opposite holds true for people who hold themselves responsible for what happens to them.

While this is an arena of research bound to expand and arrive at solutions more targeted towards mental health, there are some practical solutions to take control of our safety and keep those eerie and anxious thoughts at bay.

The Importance of a Pinch of Salt

Our safety is linked to our privacy, the more we protect our private data, the safer we are bound to feel. Other than practicing suspicion towards our emails and DMs, here are a few practical steps we can take to protect our data, and check ourselves from overthinking while we’re at it.

- Secure Your Accounts: Something as simple as utilising the Two-Step Authentication feature on your social media and bank accounts enables you to use those platforms with a password and a one-time pin only you can access.

- Secure Your Browsing: If you’re someone who frequently connects to public Wi-fi networks, using a Virtual Private Network (VPN) is a great idea. It adds an additional layer of security to your browsing.

- Safeguard Your Data in Case You Lose Your Phone: Enable the remote-tracking feature on your phone; it’s a tech boon for people who have a knack for misplacing their phone at crowded malls.

While you keep the aforementioned in mind, allow yourself the space to engage with the internet on your own terms, practice critical thinking with each stimulus you encounter online, educate those around you, and in turn, help foster a rewarding narrative of hope.

Author: Samreen Chhabra, Research Fellow at Jindal Institute of Behavioural Sciences, O.P. Jindal Global University