The Jindal School of Government and Public Policy (JSGP) offers a range of programmes that promote research and education in governance and public policy. To equip faculty and students with the skills and knowledge necessary to meet the governance challenges and improve government efficiency in India, JSGP's programmes are designed to provide students with a deep understanding of the complex issues surrounding public policy and administration.

Learn MoreStudents

University Faculty & Staff

Collaborations with International Universities

Alumni Network

Publications

The Jindal School of Government and Public Policy (JSGP) is dedicated to reinforcing research and application of governance and public policy in India and across the globe. Being an Institution of Eminence, JSGP provides a vibrant atmosphere that encourages critical thinking, multidisciplinary education, and hands-on involvement with actual issues. JSGP distinguishes itself in this way:

JSGP provides a varied spectrum of programmes meant to provide students the tools and knowledge required to succeed in public policy and governance. We provide:

Every programme guarantees that our graduates are equipped to handle modern policy issues by combining theoretical knowledge with practical application.

Embarking on your scholastic career with JSGP is a straightforward process. You may apply as follows:

After completing their application, candidates should, if they have them, send along letters of recommendation. Along with those candidates are also required to send their academic transcripts and a statement of intent.

Vibrant and fulfilling, JSGP life provides several possibilities outside of academics:

Our campus atmosphere promotes whole growth, guaranteeing that graduates are well-rounded people prepared to significantly contribute to society.

JSGP is dedicated to making sure pupils go from academic to professional life seamlessly. Our students get practical knowledge through the following:

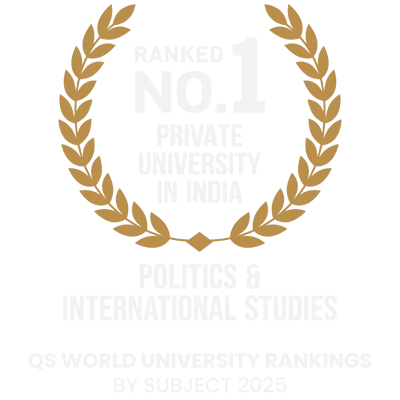

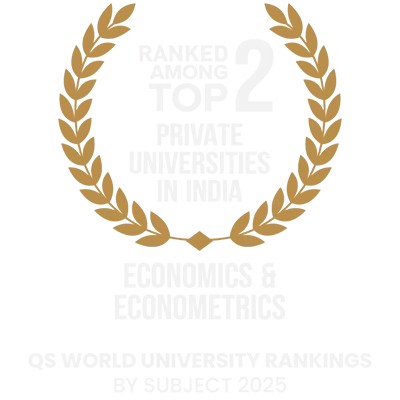

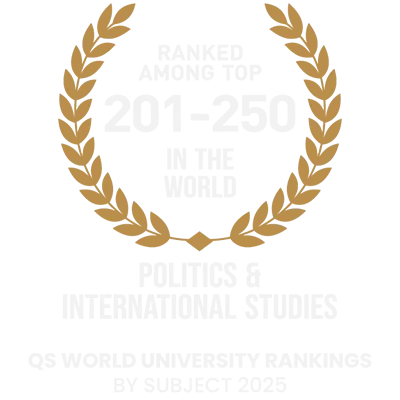

Yes, JSGP is part of O.P. Jindal Global University, which has been recognised as an Institution of Eminence by the Government of India. Our programmes are designed to meet the highest academic and professional standards.

JSGP offers:

To apply, visit our website, fill out the application form, submit the necessary documents, and follow the admission process outlined above.

We offer merit-based, need-based, and special scholarships to support students in achieving their academic goals.

The tuition fees vary by programme. Financial aid and scholarships are available to eligible students to make education more accessible.

Student life at JSGP is vibrant, with numerous academic, cultural, and social activities that create a well-rounded learning experience.

Choosing JSGP means you are choosing one of the best universities for economics and public policy in India, known for its cutting-edge research and global curriculum. Through our courses, you will be armed with the tools and knowledge to influence the future of governance and policy.