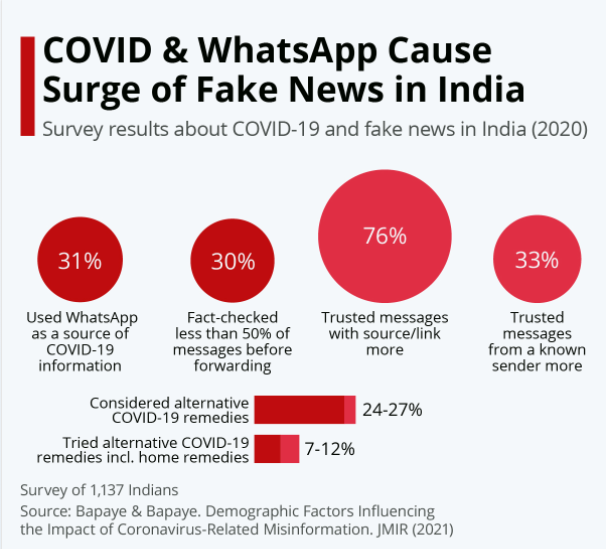

Research suggests India produced the largest amount of social media misinformation on COVID

It wasn’t very long ago when the pandemic took our sufficiently topsy-turvy world and gave it a plot twist none of us could imagine. But as plot twists usually go, this one too found its place in the larger scheme of the story.

What began with utter disbelief on our part, was soon overcome by our universal tendency to adapt. A few days after the first lockdown, pandemic-oriented vocabulary had penetrated our homes to the extent that toddlers who were previously struggling to pronounce their own names were now effortlessly using the words ‘quarantine’, ‘symptom’, ‘sanitise’ and so on.

This is what human beings do. We get exposed to what we’re afraid of, and soon enough, it becomes a part of us.

As Leah East thoughtfully explicates, “we build stories around the things we like, to make them stick around longer; and around the things we don’t like, to soften their blow. It’s one of the many ways we practice resilience.”

However, at times, the story gets bigger than us. Its magnitude can have a power over us that is often difficult to detect, let alone battle. Such is the case with conspiracy beliefs.

In the context of the pandemic, it only took us a few weeks to construct elaborate tales that deemed COVID-19 as one of China’s conspiracies to aid its mission of world domination. Another faction held the World Health Organisation as a co-conspirator, and yet another (depending on where you got your WhatsApp forwards from), considered it a Trump-iracy.

“…it is when we feel particularly uncertain, do we turn to conspiracy theories for an explanation.”

Credits: Statista

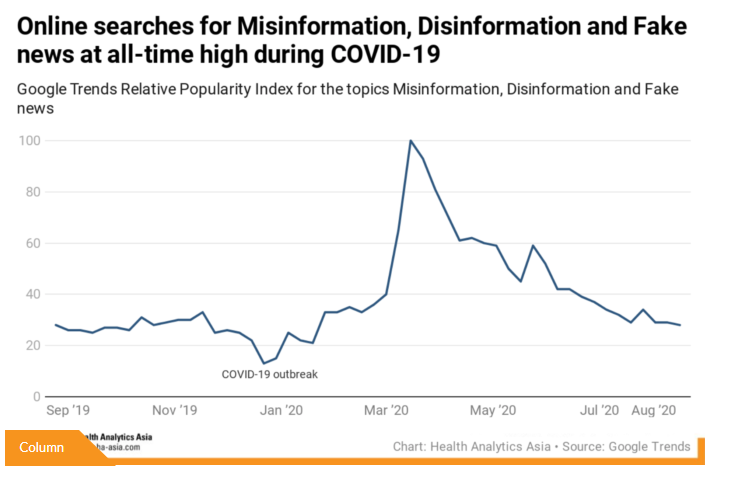

In contemporary times, as Jala Rizeq and co explain, more concerning than a dearth of information is the acquisition of unreasonable beliefs not backed by evidence. This isn’t just true for the pandemic, but rather for many of the belief systems to which we subscribe. Be it our attitude towards a new policy, the news, or even a particular group of people. It has become increasingly tempting to construe everyday occurrences as part of a bigger narrative controlled by a small group of people.

Perhaps we can attribute our indulgence in conspiracy beliefs to a phenomenon known as apophenia, or illusory pattern perception i.e our tendency to perceive meaningful connections between unrelated stimuli. While apophenia is an appealing starting point for explaining our intrigue for conspiracy beliefs, it doesn’t quite explain our commitment to them.

So why do these beliefs persist? Who is more likely to believe them, and why?

A study by Karen M. Douglas and colleagues in 2017 categorised the factors that may motivate people to engage with conspiracy beliefs as epistemic, existential or social.

Epistemic factors are concerned with people’s attempt to make sense of their environment. Hence, it is when we feel particularly uncertain, do we turn to conspiracy theories for an explanation. This can be understood with our knowledge of the surge of conspiracy theories surrounding certain periods in history such as the two World Wars, the Cold War, and most recently the Covid-19 pandemic.

Existential factors pertain to restoring a sense of security and autonomy over one’s life. Thus, a sense of powerlessness may drive us to find comfort in conspiracy beliefs.

Lastly, Social factors such as the desire to have access to information others may not have, or to think of one’s ingroup as morally right and an outgroup as the evildoer may motivate us to conform to these beliefs.

With the knowledge of what may cause these beliefs to stick around, can we minimise misinformation?

Emerging research in the field deems this as a daunting task, but not an impossible one. The mechanisms to accomplish the same are preventive, rather than antidotary. This can be traced to the fact that conspiracy beliefs operate on a vulnerable cognitive state and can thus solidify into strong attitudes, which in turn, are hard to dispute.

The provision of factual information along with warnings that prepare people to expect misinformation can act as an effective tool against the propagation of conspiracy theories. On a personal scale, reading those WhatsApp forwards with a pinch of salt, and verifying content before forwarding is the key here.

At a more fundamental level, the development and encouragement of critical thinking within educational ecosystems can go a long way in how we approach, synthesise, perceive and share information.

In sum, we’re guided by an inherent tendency to detect patterns in randomness, find a sense of solace in narratives that support those patterns and seem to be controlled by others; and yet we’re somehow supposed to call them out by trusting our own rationale?

That’s quite a bucketload.

One could almost say our evolutionary mechanisms have conspired against us, but we know better than that now. Don’t we?

Author: Samreen Chhabra, Research Fellow at Jindal Institute of Behavioural Sciences, O.P. Jindal Global University