The 21st century, oft referred to as the Asian century in international politics is so called owing to the rise of powerful economies from what was once seen as the ‘Orient’. Countries in Northeast Asia, be it the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Japan, Republic of China (ROC)/ Taiwan, South Korea or North Korea exert myriad types of influences on the international system. The various types of relationships among the countries of the Northeast Asian region also impact international politics as these range from conflicts over disputed islands, espionage, perceived historical injustices such as the Nanjing massacre to rising volumes of trades in the region to potential nuclear crises to balancing between acts of cooperation and conflict. The history, culture, society and politics, all of which are different from that of the Western world become interesting aspects of study as all of these impact the posturing of the countries of the region in their respective foreign policies. Given the fact that India has active conflicts as well as partnerships with countries of the region, a better understanding of Northeast Asia from the lenses of security to economics to diplomacy to culture becomes pertinent. The Centre for Northeast Asian Studies looks at the countries of the region with fine lenses to offer understandings beyond what is provided by Western literature and theories of international politics. Tools such as track 2 discussions, seminars, lectures, primary research, historical and archival studies, along with a reliance on the languages of the region are used to understand international relations.

Book Chapters:

Pathak, Sriparna (2021) "The Chinese Concept of Sovereignty and the India-China Border Dispute", in Re-Imagining Border Studies in South Asia edited by Dr. Dhananjay Tripathi, Routledge, ISBN 9781032189482.

Pathak, Sriparna (2021) "Xi Jinping's China Dream and the future graph of the Chinese economy", in Chinese Politics and Foreign Policy Under Xi Jinping, edited by Arthur S. Ding and Dr. Jagannath P. Panda, Routledge, ISBN 9780367470289.

Book Review

Online Publications:

Editorials/ Newspaper Articles

Anushka Saxena

Anushka Saraswat

Anubhav Shankar

Divyanshu Jindal

Palak Maheshwari

Dnyanashri

Yukti Panwar

Sukanya Bali

Harsheen Sahni

B.S Ashish

Part 1 : https://standpointindia.in/what-makes-the-yemeni-crisis-one-of-a-kind-part-1/

Part 2 : https://standpointindia.in/what-makes-the-yemeni-crisis-one-of-a-kind-part-2/

Ashish, B.S. "Can Erdögan's Turkey really help the Uighurs in Xinjiang?" The Kootneeti (2021). https://thekootneeti.in/2021/10/16/can-erdogans-turkey-really-help-the-uighurs-in-xinjiang/

Korea Fair in India - Delhi 2021

By Palak Maheshwari

The Naadam Festival: Bastion of Mongol Solidarity

by Anurag Sharma

Taru Ahluwalia_From Namaste to Annyeong Indias Hangul Day Celebrations

Saesang - Exploring The Koreas

CNEASNewsletter Vol 1, Issue 1

CNEAS Newsletter Vol. 1 Issue 2

CNEAS Newsletter Vol. 1 Issue 3

CNEAS Newsletter Vol. 1 Issue 4

CNEAS Newsletter Vol. 1 Issue 5

Formosa Watch Newsletter

Dr. Manoj Kumar Panigrahi

Assistant Professor, Director, Centre for Northeast Asian Studies

Dr Manoj Kumar Panigrahi is an Assistant Professor and Director, of the Centre for Northeast Asian Studies at the Jindal School of International Affairs. Dr Panigrahi holds a bachelor's in political science from Berhampur University, Master's degree in Diplomacy, Law, and Business from O.P. Jindal Global University (India). He was a recipient of Taiwan's Ministry of Education Scholarship to pursue doctoral studies. He completed his PhD at National Chengchi University (Taiwan). He was a Research Fellow and currently serves as a Non-resident Fellow at Taiwan NextGen Foundation, Taipei.

His research interests include ethnic conflicts, foreign policy, and the culture of Indo-Pacific countries. His PhD dissertation examined the role of mediators in separatist movements in a comparative context. His research also focused on exploring the causation behind the formation of factions in armed ethnic groups and how they impact the peacemaking process.

Dr Panigrahi regularly writes for several of Taiwan's print media. He contributes to a bilingual blog column where he writes and promotes Indian culture in Taiwan.

He has been invited to more than 101 schools and universities across Taiwan, amounting to more than 300 lectures so far. He has received the Best Scholarship Recipient Student award from Taiwan's Ministry of Education Scholarship (2016-2020) for his work on sharing Indian culture at the grassroots level in Taiwan.

He offers courses on Conflict Management, Cross-Strait Relations, East Asian Politics and, Taiwanese History, Culture and Politics.

Our Founder: Dr. Sriparna Pathak is an Associate Professor in the Jindal School of International Affairs of O.P. Jindal Global University, Haryana, India. She teaches courses on Foreign Policy of China as well as Theories of International Relations. Her previous work experience covers Universities like Gauhati University, Don Bosco University; the Ministry of External Affairs, where she worked as a Consultant for the Policy Planning and Research Division, working on China's domestic and foreign polices; think tanks like Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi and Kolkata respectively, South Asia Democratic Forum in Brussels where she is a Research Fellow and the Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research in New Delhi where she worked as a researcher. She has also worked for UNICEF, Madhya Pradesh, researching on governmental educational and medical interventions and impacts on communities.

Awarded a Doctorate degree from the Centre for East Asian Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in 2015, Dr. Pathak is fluent in English, Mandarin and Indian languages like Hindi, Bengali and Assamese.

She has been a recipient of the joint fellowship awarded by the Ministry of Human Resources Development, India and the China Scholarship Council, Government of the People's Republic of China, and she spent two years in China, actively researching various aspects of China's domestic economy. Her areas of interest are China's domestic economy, trade and economic relations between India and China and China's foreign policy and economic linkages with the world.

Dr. Pathak has written more than a dozen chapters in various books on China, the publishers of which include Routlege, Sage and Pentagon among others. Her journal publications include Journal of Contemporary Chinese Political Economy and Strategic Relations, National Sun-Yat Sen University, Taiwan to Journal of Indo Pacific Perspectives of Air University of the U.S. Air Force. She has also been a guest speaker at several think tanks in India and abroad and has been interviewed by media organisations ranging from Sankei Shimbun to Huffington Post to South China Morning Post to The Star, Toronto to Associated Press, Beijing among others. She has also been part of several panels and talk shows in India and in the PRC respectively.

She is currently working on a project on India's Act East Policy and China's responses. She is also conducting various types of research on insurgency and China's support to it in Northeast India. She has been a resource person for various media organisations, colleges, Universities and think tanks within India and abroad. Dr. Pathak firmly believes in the necessity for using specialised knowledge, relying on primary sources on countries of Northeast Asia for strengthening India's international relations.

Director: Dr. Manoj Kumar Panigrahi

Dr. Manoj Kumar Panigrahi is an Assistant Professor at the Jindal School of International Affairs. Dr. Panigrahi holds a Bachelors in Political Science from Berhampur University, Master's degree in Diplomacy, Law, and Business from O.P. Jindal Global University (India). He was a recipient of Taiwan's Ministry of Education Scholarship to pursue doctoral studies. He completed his Ph.D. from National Chengchi University (Taiwan). He was a Research Fellow at Taiwan NextGen Foundation based in Taipei, Taiwan.

His research interests include ethnic conflicts, foreign policy, and the culture of Indo-Pacific countries. His Ph.D. dissertation examined the role of mediators in separatist movements in a comparative context. His research also focused on exploring the causation behind the formation of factions in armed ethnic groups and how they impact the peacemaking process.

Dr. Panigrahi regularly writes for several of Taiwan's print media. He contributes to a bilingual blog column where he writes and promotes Indian culture in Taiwan.

He has received the Best Scholarship Recipient Student award from Taiwan's Ministry of Education Scholarship (2016-2020) for his work on sharing Indian culture at the grassroots level in Taiwan. He has been invited to more than 100 schools and universities across Taiwan, amounting to more than 150 lectures so far.

Centre Coordinator Rakshith Shetty, MADLB 2022

Rakshith Shetty is the centre coordinator of CNEAS. He majored in Business Administration from Christ University, Bangalore. He is currently a student of MA Diplomacy, Law and Business from JSIA. His interests include Chinese Foreign Policy, International Business and Finance, Corporate Threat Intelligence, Geopolitical Risk Intelligence and Cybersecurity. He is a regular contributing writer for the Defence and Security Alert Magazine, Delhi. He has also contributed to various organisations, including Vivekananda International Foundation and ORCA.

Organised a guest lecture by Dr. Manjari Singh, Amity University on ‘China’s Strategic Ambitions in the Middle East’, on April 29, 2023, for O.P. Jindal Global University.

Organised an online talk on ‘Taiwan’s- EU Foreign Policy on April 13 for O.P. Jindal Global University

.jpg)

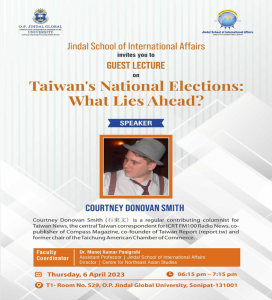

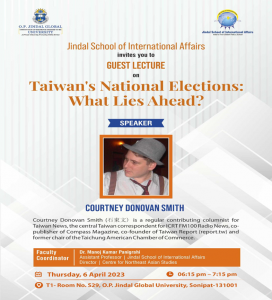

Organised a guest lecture by Courtney Donovan Smith, Co-founder, Taiwan Report, contributing columnist, Taiwan News on ‘Taiwan’s National Elections: What Lies Ahead.’ Dated: April 6, 2023

Organised an essay writing competition for the students at the Jindal School of International Affairs, in collaboration with Loop Media, between April 4, 2023 – May 4, 2023.

Organised a lecture by Prof. Pradeep Taneja, University of Melbourne on ‘Australia- China relations’, on April 4, 2023, at O.P. Jindal Global University.

Organised an online conference on ‘The Indo-Pacific and International Relations under the Sino-US Competition.’ Dated: March 17, 2023

Organised a visit to The Philippines Embassy in Delhi for an intensive educational experience on February 20, 2023, at O.P. Jindal Global University

Centre for Northeast Asian Studies Webinar Report on ‘The post-Covid 19 world order and Northeast Asia’ 12 November 2021

Report

Anubhav Shankar Goswami

Research Assistant, Centre for Northeast Asian Studies

Jindal School of International Affairs

O.P Jindal Global University

Email: asgoswami@jgu.edu.in

Divyanshu Jindal

Research Assistant, Centre for Northeast Asian Studies

Jindal School of International Affairs

O.P Jindal Global University

Email: djindal@jgu.edu.in

Centre for Northeast Asian Studies, a dedicated platform by Jindal School of International Affairs (JSIA) for research on Northeast Asia, organized its inaugural webinar – The post-Covid 19 world order and Northeast Asia – on 12 November 2021.

The event started with the opening remarks delivered by Professor and Dean of JSIA, Dr. Sreeram Chaulia. He extended a warm welcome to all the participating eminent scholars – Ambassador Vishnu Prakash, Ex Envoy / Ambassador to Canada & South Korea Foreign Office Spokesman, Prof. Purnendra Jain, Emeritus Professor, Department of Asian Studies. The University of Adelaide, Prof. Yee-Kuang Heng, Graduate School of Public Policy, The University of Tokyo, Ayae Yashimoto, Researcher, Formerly at National Chengchi University, Dr. Young Chul Cho, Associate Professor, School of International Studies, Jeonbuk National University, Ikue Kawauchi, Researcher and Consultant Bangera’s Global Consulting Inc. Tokyo, Prof. Mumin Chen and Naina Singh, Professor, National Chung Hsing University of Taiwan/Doctoral Candidate, National Chung Hsing University of Taiwan, Dr. Raymond Lau, Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science and Sociology, North South University (NSU) and Dr.Fang Tien-tze, Associate Professor, National Tsing Hua University.

The webinar began with a keynote speech by Ambassador Prakash who spoke about the persistent lack of American resolve in challenging Chinese belligerence from trade to geopolitics. When asked about possible American commitment of defending Taiwan from Chinese forceful unification, Ambassador Prakash opined that such an assurance looks bleak due to poor political and military resolve of the U.S in calling out China’s aggressions in recent years.

The keynote speech was followed by the first session on Japanese and South Korean views on post-Covid world order. The session was moderated by Dr. Jabin Jacob.

The first speaker of the session Prof. Purnendu Jain argued that in a post-covid world, Japan’s ability to juggle between engaging China economically to balancing China by way of security cooperation with the U.S will be increasingly difficult. Prof. Jain said that China’s numerous punitive actions against Japan like the ‘weaponisation’ of supply chain to hurt Japanese economy has forced Tokyo to pursue a tighter embrace of U.S both economically and militarily. On the question of economic security that has gained renewed focus due to supply chain disruption by Covid-19, Ayae Yashimoto talked about how Japan is trying to enhance its economic security deterrence by making other countries recognize that Japan is economically “indispensable.” Yoshimoto said that by expanding Japan’s presence in the global supply chain, Tokyo intends to achieve indispensability. On the other hand, Prof. Yee-Kuang Heng talked about how Japan is deepening its ties with Britain to diversify its defense and economic ties keeping in mind the unfolding uncertainty of the post-covid world that requires greater flexibility in foreign policy. He highlighted some of the recent key events in their bilateral relations like an agreement between the two nations to comments formal negotiations on Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) to deepen the defence relationship. The session also shifted to a discussion on India-Japan relations. Ikue Kawauchi, an experienced operator of India-Japan relations, pointed how Japanese companies can leverage an India on the cusp of economic leapfrogging to achieve economies of scale.

Putting his country’s view on the emerging post-covid world order, Dr. Young Chul Cho of South Korea said that young South Koreans want continuity of the liberal international world order. Talking more on the matter, Dr Cho said that this commitment to liberal values put young South Korean at odds with illiberal impulses of Beijing. Therefore, South Korean youths have strong anti-Beijing views and feels China’s rise is a threat to liberal values. The session concluded with a brief discussion on the raised points by the panelists and a short Q&A session.

The second session revolved around the perspectives from Taiwan and Hong Kong. The session was chaired and moderated by Prof. Srikanth Kondapalli. The panel for the session consisted of Prof Mumin Chen, Ms. Naina Singh, Dr. Raymond Lau, and Dr. Fang Tien-tze.

Organised a guest lecture by Dr. Manjari Singh, Amity University on ‘China’s Strategic Ambitions in the Middle East’, on April 29, 2023, for O.P. Jindal Global University.

Organised an online talk on ‘Taiwan’s- EU Foreign Policy on April 13 for O.P. Jindal Global University

Organised a guest lecture by Courtney Donovan Smith, Co-founder, Taiwan Report, contributing columnist, Taiwan News on ‘Taiwan’s National Elections: What Lies Ahead.’ Dated: April 6, 2023

Organised an essay writing competition for the students at the Jindal School of International Affairs, in collaboration with Loop Media, between April 4, 2023 – May 4, 2023.

Organised a lecture by Prof. Pradeep Taneja, University of Melbourne on ‘Australia- China relations’, on April 4, 2023, at O.P. Jindal Global University.

Organised an online conference on ‘The Indo-Pacific and International Relations under the Sino-US Competition.’ Dated: March 17, 2023

Organised a visit to The Philippines Embassy in Delhi for an intensive educational experience on February 20, 2023, at O.P. Jindal Global University

Centre for Northeast Asian Studies Webinar Report on ‘The post-Covid 19 world order and Northeast Asia’ 12 November 2021

Report

Anubhav Shankar Goswami

Research Assistant, Centre for Northeast Asian Studies

Jindal School of International Affairs

O.P Jindal Global University

Email: asgoswami@jgu.edu.in

Divyanshu Jindal

Research Assistant, Centre for Northeast Asian Studies

Jindal School of International Affairs

O.P Jindal Global University

Email: djindal@jgu.edu.in

Centre for Northeast Asian Studies, a dedicated platform by Jindal School of International Affairs (JSIA) for research on Northeast Asia, organized its inaugural webinar – The post-Covid 19 world order and Northeast Asia – on 12 November 2021.

The event started with the opening remarks delivered by Professor and Dean of JSIA, Dr. Sreeram Chaulia. He extended a warm welcome to all the participating eminent scholars – Ambassador Vishnu Prakash, Ex Envoy / Ambassador to Canada & South Korea Foreign Office Spokesman, Prof. Purnendra Jain, Emeritus Professor, Department of Asian Studies. The University of Adelaide, Prof. Yee-Kuang Heng, Graduate School of Public Policy, The University of Tokyo, Ayae Yashimoto, Researcher, Formerly at National Chengchi University, Dr. Young Chul Cho, Associate Professor, School of International Studies, Jeonbuk National University, Ikue Kawauchi, Researcher and Consultant Bangera’s Global Consulting Inc. Tokyo, Prof. Mumin Chen and Naina Singh, Professor, National Chung Hsing University of Taiwan/Doctoral Candidate, National Chung Hsing University of Taiwan, Dr. Raymond Lau, Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science and Sociology, North South University (NSU) and Dr.Fang Tien-tze, Associate Professor, National Tsing Hua University.

The webinar began with a keynote speech by Ambassador Prakash who spoke about the persistent lack of American resolve in challenging Chinese belligerence from trade to geopolitics. When asked about possible American commitment of defending Taiwan from Chinese forceful unification, Ambassador Prakash opined that such an assurance looks bleak due to poor political and military resolve of the U.S in calling out China’s aggressions in recent years.

The keynote speech was followed by the first session on Japanese and South Korean views on post-Covid world order. The session was moderated by Dr. Jabin Jacob.

The first speaker of the session Prof. Purnendu Jain argued that in a post-covid world, Japan’s ability to juggle between engaging China economically to balancing China by way of security cooperation with the U.S will be increasingly difficult. Prof. Jain said that China’s numerous punitive actions against Japan like the ‘weaponisation’ of supply chain to hurt Japanese economy has forced Tokyo to pursue a tighter embrace of U.S both economically and militarily. On the question of economic security that has gained renewed focus due to supply chain disruption by Covid-19, Ayae Yashimoto talked about how Japan is trying to enhance its economic security deterrence by making other countries recognize that Japan is economically “indispensable.” Yoshimoto said that by expanding Japan’s presence in the global supply chain, Tokyo intends to achieve indispensability. On the other hand, Prof. Yee-Kuang Heng talked about how Japan is deepening its ties with Britain to diversify its defense and economic ties keeping in mind the unfolding uncertainty of the post-covid world that requires greater flexibility in foreign policy. He highlighted some of the recent key events in their bilateral relations like an agreement between the two nations to comments formal negotiations on Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) to deepen the defence relationship. The session also shifted to a discussion on India-Japan relations. Ikue Kawauchi, an experienced operator of India-Japan relations, pointed how Japanese companies can leverage an India on the cusp of economic leapfrogging to achieve economies of scale.

Putting his country’s view on the emerging post-covid world order, Dr. Young Chul Cho of South Korea said that young South Koreans want continuity of the liberal international world order. Talking more on the matter, Dr Cho said that this commitment to liberal values put young South Korean at odds with illiberal impulses of Beijing. Therefore, South Korean youths have strong anti-Beijing views and feels China’s rise is a threat to liberal values. The session concluded with a brief discussion on the raised points by the panelists and a short Q&A session.

The second session revolved around the perspectives from Taiwan and Hong Kong. The session was chaired and moderated by Prof. Srikanth Kondapalli. The panel for the session consisted of Prof Mumin Chen, Ms. Naina Singh, Dr. Raymond Lau, and Dr. Fang Tien-tze.

Prof Kondapalli started the session by thanking Prof. Pathak and the Centre for Northeast Asian Studies. He highlighted the statistics regarding the COVID-19 infections in Northeast Asian states, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and India. Prof Chen focused on the Taiwanese situation pertaining to the pandemic. He explained how lack of international support and absence of WHO membership has affected Taiwan’s response to the pandemic, despite being the first one to discover and inform about the COVID-19. Ms. Naina raised the point of ‘health’ becoming a part of political discourse in Taiwan to understand why Taiwan reacted to the pandemic the way it did. She emphasized on the point that Taiwan has taken important cues from the SARS pandemic to formulate policy and strategy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Dr. Lau discussed the showdown between the Chinese BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) and the Indo-Pacific in the post COVID-19 world order. He highlighted that China’s foreign policy is driven by Beijing’s desire to demonstrate its self-confidence and belief that China can offer a model of economic development as an alternative to western model for the world. He further opined that the current Chinese premier Xi Jinping has led to a radical departure of the three-decade logic of ‘keeping a low profile’ under former leader Deng Xiaoping. Today, the core concept is ‘national rejuvenation’. The next panelist- Dr. Fang, outlined the Chinese Foreign Policy, policy under Xi Jinping, and implications for Indo-Pacific. He explained the various factors which construct the Chinese foreign policy, and the legacy of Deng Xiaoping’s thought. He raised the topics of Xi’s Chinese Dream, Xi Jinping’s Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics of a New Era, the advent of the ‘Chinese Century’, and the Chinese perception of the world. He also highlighted ‘ping shi’ diplomacy- The world view from an equal footing. He argued how despite commitments to the peaceful development, China has not shown considerable actions toward peaceful resolution to territorial disputes. China’s wolf warrior diplomacy was also discussed by multiple panelists, which led to the conclusion of how China has failed to build a benign image of China’s contribution to the world through propaganda.

The session concluded with Dr. Pathak summarizing the key points raised throughout the event by the panelists and what India can learn from the experiences of Northeast Asia for the post-COVID-19 world order. The roundtable event concluded with Dr. Panigrahi delivering the vote of thanks to all the panelists, scholars, and attendees.

Director: Dr. Sriparna Pathak, Associate Professor, Jindal School of International Affairs

EMAIL: spathak@jgu.edu.in

Phone Number: +91 9051964100

Twitter: @Sriparnapathak

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/sriparnapathak

Director: Dr. Manoj Kumar Panigrahi, Assistant Professor, Jindal School of International Affairs

EMAIL: mkpanigrahi@jgu.edu.in

Phone Number: +91 7419748976

Twitter: @manojkupani

Rakshith Shetty - 22jsia-rshetty@jgu.edu.in