Written by: Dia Saxena

Ashima’s story in The Namesake follows the archetype of dislocation and alienation experienced by most first-generation immigrants. She moves to the United States after marrying Ashoke, where the cultural dislocation she experiences is particularly poignant. The movie lucidly presents the contrast between the lively streets of Kolkata and the quiet suburban settings in the United States, providing a backdrop to her deep isolation. She walks down the empty, snow-covered streets, capturing her deep loneliness and the unforgiving surroundings of this unfamiliar landscape. Her seclusion has crossed the physical barriers and marched into emotional dimensions as well.

Her desperate attempts at reproducing the comfort of Bengali culture in her American home by wearing traditional sarees, cooking Bengali dishes, and rearing the children with Bengali Customs Act as minor acts of resistance against the overpowering force that is the dominating American culture. On the other hand, however, these same efforts signal the cultural fissure separating her from her surroundings. Ashima finds little common interest with her American neighbors, and cultural differences inhibit her from making meaningful contacts outside the circle of Bengali immigrants. Her isolation is a model of acculturation whereby “members of the first generation may feel unable to participate in the host culture without some sense of loss of identity”.

Gogol’s Name: The Symbol of Dual Identity

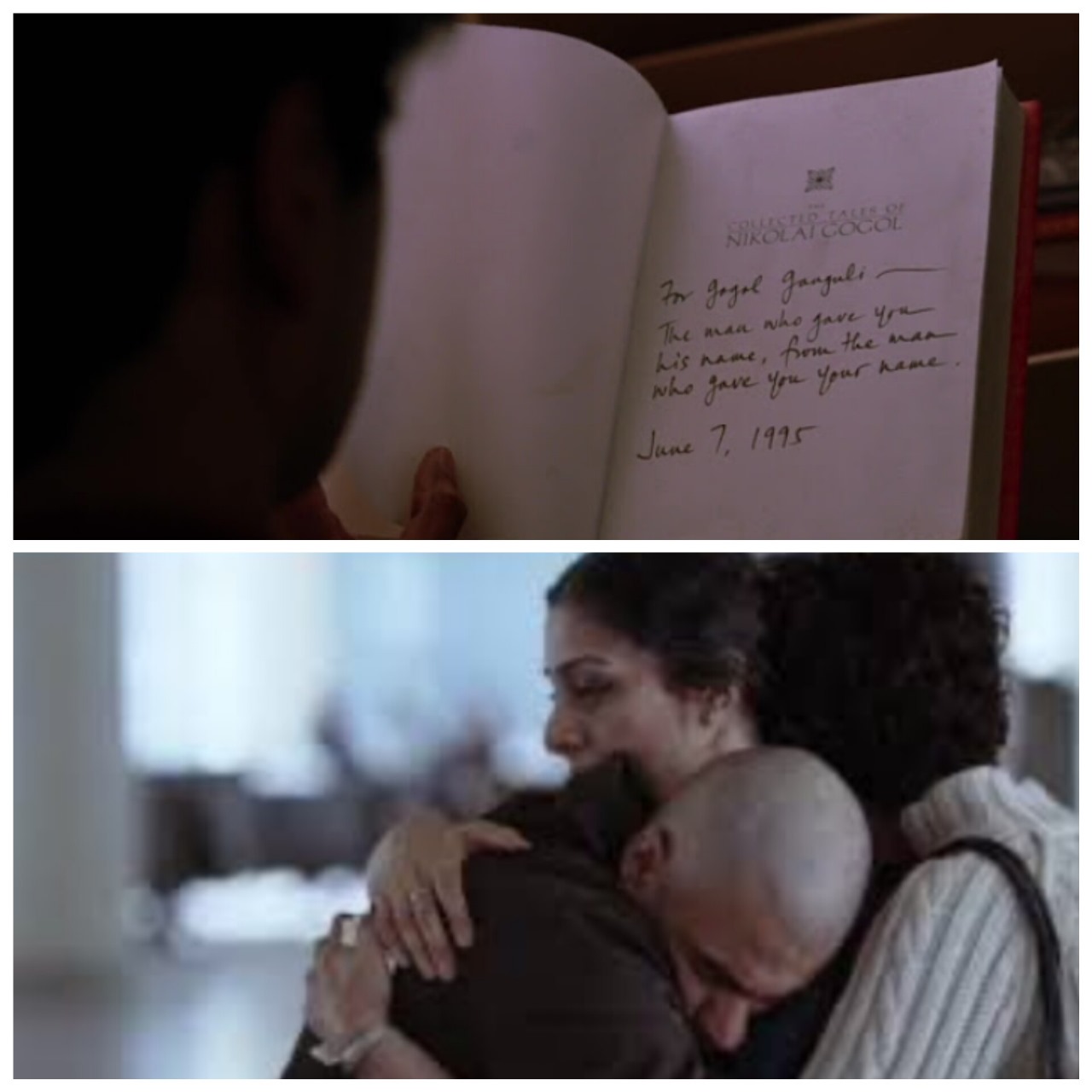

The symbolic meaningfulness of the name Gogol in The Namesake is an identity turmoil that, from the very beginning, is deeply interconnected with the theme of acculturation. The name Gogol, attributed by his father to the great Russian writer Nikolai Gogol, becomes increasingly an underlying nuisance as he grows up in America. The name Gogol, which he received from his father in honor of the Russian writer, becomes an increasing burden as he grows up in America. His classmates find the name strange and one-of-a-kind, adding to Gogol’s alienation. His name is part of what he struggles with almost throughout the book as he balances his cultural Bengali heritage with his desires to conform to the American social lifestyle. Throughout his childhood, Gogol disidentified with his name and thereby with his cultural heritage. His discomfort with his name reflects his broader discomfort with his dual identity. As a second-generation immigrant, Gogol finds himself torn between two worlds: no longer fully Bengali, as his parents are; not yet fully American, as his classmates already are. This is in greater conflict when he decides to legally change his name to Nikhil, a title that he believes will better help him fit into American culture. Nevertheless, the act

of renaming himself fails to alleviate Gogol’s internal turmoil. Rather, it exacerbates his crisis of identity, as he realizes that altering his name does not eliminate the cultural legacy that continues to influence his existence. In the end, the name “Gogol” becomes a metaphor for Gogol’s journey toward self-acceptance. The acceptance is a reconciliation with his identity and serves to confirm that the acculturation process for second-generation immigrants is often not just about assimilation into the host culture but also about confronting the heritage they once wished to discard.

Generational Conflict

The generational gap that exists between the representative first-generation immigrants, Ashoke and Ashima, and their offspring, Gogol and Sonia, as second-generation immigrants, form an important aspect of The Namesake. This tension forms a highlight of the different ways of acculturation and assimilation that immigrant parents adopt compared to their children. For Ashoke and Ashima, their cultural heritage is an integral part of who they are, and they strive to pass along Bengali customs to their children. They raise Gogol and Sonia in a Bengali- speaking household, sending them to Bengali cultural events while remaining close with other Bengali families.

Growing up in the U.S., however, the children do not feel quite the same attachment to these traditions. Gogol, especially, resists his parents’ efforts to ingrain a Bengali identity into his life. He feels more a part of American culture and often finds his parents’ cultural practices to be irrelevant or old-fashioned. This cultural dissonance is eloquently reflected in different pivotal scenes of the movie, where Gogol expresses his discontent regarding the traditional Bengali practices to a family gathering or when he starts a romantic relationship with Maxine, who is a rich American woman representing his ultimate attempt at complete assimilation into American culture. His relationship with Maxine can be seen as an act of rebellion against the cultural expectations of his parents, as he completely surrenders to her world, which is absolutely devoid of anything Bengali. Nevertheless, like most intergenerational conflicts, this too was multidimensional. As Gogol grows, he also comes to appreciate the sacrifices his parents made as immigrants and understands the importance of his cultural heritage. His father’s sudden death binds him back to his identity through which he reconnects to his roots concerning his Bengali heritage. This is a reconciliation between generations that underlines the uneasiness of acculturation-the situation when second-generation immigrants have to choose between cultural values inculcated by their parents and the standards of the immediate surroundings.

Hybridity and the resolution of identity

The central emotional journey in The Namesake deals with Gogol’s journey toward self-acceptance and the resolution of his identity crisis. Early on, Gogol shows his unease with his bicultural heritage and strangeness first by his parents’ Bengali culture and then by the American culture he has grown up in. His penchant for changing his name, as well as his attempt at a purely American experience through his relationship with Maxine, are attempts to resolve this dissonance by prioritizing one cultural paradigm over the other. As the narrative of the film unfolds, Gogol comes to the understanding that his identity cannot be simplistically categorized into two distinct cultural frameworks. His father’s death proves to be a pivotal catalyst in his realization of this issue, and it is then that he is forced to rethink the relationship he has built with his own cultural identity. The resolution of Gogol’s naming when he concludes by embracing his naming and reconnecting with his Bengali heritage marks the end of his assimilation process. The resolution of Gogol’s identity crisis doesn’t depend on choosing between being Bengali or American; it is a matter of recognizing that he is both of these things. This is the idea of hybridity, of dual identity, that underlines the entire film, in fact, and indeed often with

the immigrant experience: a new, hybrid identity forms that combines elements of both the native and the assimilated culture. Gogol’s ultimate embracing of his mixed identity points toward the overarching

concept of acculturation, whereby the amalgamation of cultures, in a way, gives way to an even more elaborate and involved understanding of one’s identity. The movie, through its portrayal of the characters Ashima, Ashoke, and Gogol, emphasizes that such an experience has intricate emotional, cultural, and

generational challenges. It shows that acculturation is not a one-way process but rather a continued negotiation between an individual’s cultural heritage and the impositions put on by an alienated society.

The way Ashima’s isolation gives way to cultural assimilation, the problem of Gogol’s name and identity, and the intergenerational battle that is waged within the Ganguli family represent some important examples of the challenges and opportunities presented by acculturation. The characters ultimately show that one can take the best of both worlds but retain their core and, in that sense, hybrid identities may prove to be a source of strength and resilience. Acculturation in The Namesake, has been fundamentally an individualistic and gradual process. It captures the reality that, for immigrants and their children, identity is fluid, emerging and changing in ongoing response to the surrounding cultural environment.