Gaps In the System: Addressing the Challenges of Drug Enforcement in India

May 5, 2025 2025-05-05 9:55Gaps In the System: Addressing the Challenges of Drug Enforcement in India

Gaps In the System: Addressing the Challenges of Drug Enforcement in India

By Akash Namboodiripad

Abstract

This article examines India’s strategic challenges in narcotics regulation, analysing its geographical vulnerability between major drug-producing regions and the escalating production in Myanmar following political instability. It critiques the limitations of India’s legislative framework, particularly the NDPS Act’s failure to distinguish between different types of offenders and address sophisticated trafficking networks. The article also highlights emerging digital drug markets and emphasises the importance of enhanced enforcement capabilities to meet India’s sustainable development goals.

Historical and Geographical Relevance

The etymology of narcotics can be traced back to the ancient Greek medicant Hippocrates, who used the word narcosis to describe a state of benumbing or deadening. He is purportedly said to have used opium as an anaesthetic in his primordial medical procedures. Kautilya’s Arthashastra elaborates on the different effects of herbs and poisons that the king should be aware of. The use of intoxicating and addictive substances predates scriptural history and has remained embedded in our cultural sphere for millennia.

Considering its known dual use throughout the centuries, societies have also grappled with the medical application of narcotics on one hand and abuse on the other. The supply and cultivation of drugs meant for medicinal or ritual use, such as opium or cannabis, have evolved into complex trafficking systems that are entrenched in traditional and contemporary networks that span across the length of the subcontinent. India’s strategic location at the crossroads of the Golden Crescent and Golden Triangle places it in a precarious position. Overlapping supply routes expose Indian law enforcement to a deadly combination of the two drug dens, each vying for dominance in the region. While not legally binding, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) target 3.5 that seeks to strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol, obligates India to pursue effective enforcement within its territories.

Regional Realities

As of 2024, the Taliban regime has reportedly cracked down on opium cultivation, likely driving an increase in opioid supply from Myanmar. Along with this, Myanmar is also finding a foothold in synthetic drug production, with a surge in Amphetamine Type Stimulant (ATS) drugs such as amphetamine, methamphetamine and ephedrine. While it is a myth that natural drugs are much safer, some synthetics can be potent and have unpredictable effects and an expanding inventory of addictive substances inherently makes regulation and enforcement much more tougher.

The competition for control over drug trafficking routes is deeply entangled with the conflict in Manipur, as most armed groups rely on revenue through drug trades, supplementing extortion with direct collaboration and facilitation of Myanmar-based drug cartels. Myanmar’s ongoing state of lawlessness, ever since the Military Junta took control in 2021, has only exacerbated the crisis, as rising costs have forced farmers in the Shan and Kachin states to cultivate poppy to survive.

According to the Opium Survey conducted by the UNODC and the Myanmar Government 2022, Myanmar has seen an increase of 33% in opium cultivation area to 40,100 hectares, and an 88% increase in potential yield to 790 metric tonnes. Added to that, the increasing production of ATS as a viable alternative.

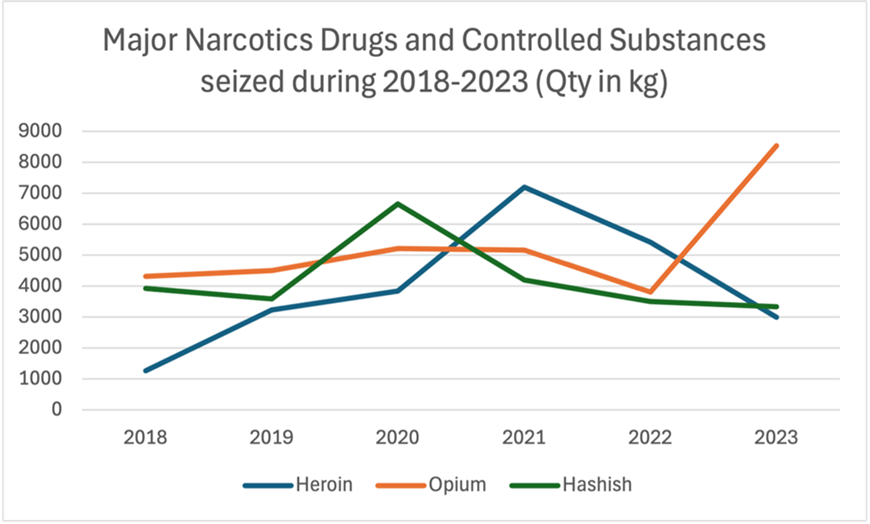

As shown in Fig (1), there is a significant spike in the seizure of opium from late 2021, likely attributing to the increase in production catalysed by the instability in Myanmar. The Indian state has been actively monitoring this issue and its links to the ongoing conflict in Manipur. The recent declaration of President’s Rule over the state is being speculated to be a strategic move in the right direction.

Limitations of the NDPS Act and Enforcement Agencies

It is in this context that India should seek to optimise its teetering yet draconian piece of legislation that is the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act of 1985. The NDPS Act is the primary jurisprudential document that prohibits, except for medical or scientific purposes, the manufacture, production, trade, use, etc., of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances. It, however, misses a major piece of enforcement with its focus on small-time traffickers but does not outline prosecution and law enforcement on extensive drug cartels, which are the new reality of narcotics proliferation in the region. The Act, and by extension, statutory agencies such as the Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) and the lesser-known Central Bureau of Narcotics (CBN), while acknowledging the amount/quantity of contraband peddled and classifying them, do not categorically draw any distinction between everyday addicts, small-time peddlers and large traffickers.

This law does not equip or lay down any procedure for the Indian law and order establishment to work closely with the armed forces to tackle imminent threats that are linked with drug financing and trafficking. The NCB, like most other Indian agencies, used to work in relative isolation and therefore seldom worked in coordination with the state police and the customs department, thereby establishing a weak link that is ripe to be exploited. This was, however, largely rectified by the NCORD (National Narcotics Coordination Portal) with its 4 tier mechanism of real time coordination.

Digital Drug Markets

There also exists the domain of digital drug markets, which are increasingly difficult to track and identify. The online drug market, despite being a volatile one, provides surprising quality of service, and consistently weeds out underperformers. Dark web anonymous drug platforms, such as the infamous Silk Road, provide detailed time series data on products along with prices and rated transactions by scraping their websites. Ross Ulbricht, creator of Silk Road, was recently pardoned by the Trump Administration citing the case as an instance of government overreach despite prosecutors stating that the website sold $200 million worth of drugs anonymously.

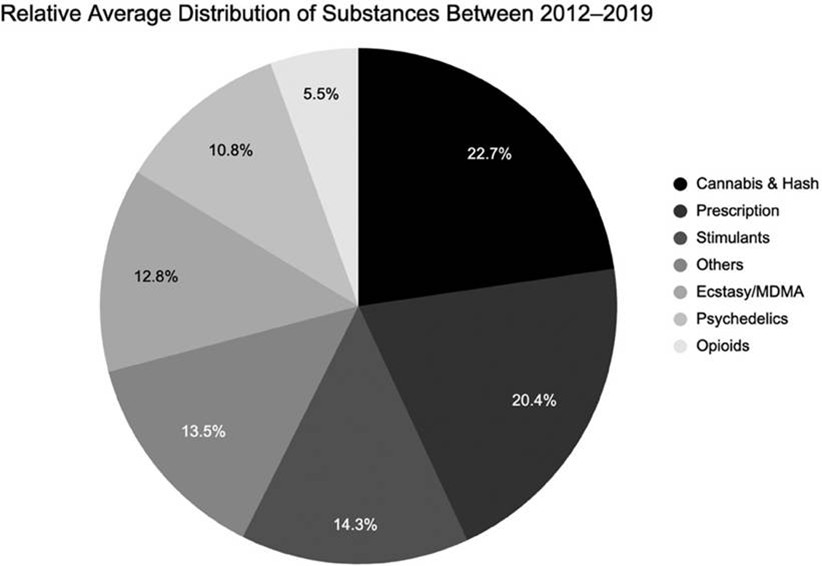

Fig. (2): Visualisation of the chronological substance distribution on the Dark Web.

Indian agencies struggle with expertise to conduct cyber investigations that cover the scope of the dark web where transactions are made through cryptocurrency. As late as December 2024, the Delhi Crime Branch managed to bust a cartel operating through the dark web by seizing a cache of cannabis worth Rs 2 crore ahead of the Delhi Assembly Elections. With an expanding base of internet users, digital drug enforcement remains an imperative that the Indian state must direct its energies towards.

Conclusion

In a world that is increasingly gaining access to drugs, prescription or otherwise, regulating its production and use is critical to achieving sustainable development as outlined through SDG target 3.5. As India moves up the income ladder, it is critical for it to lead the charge against substance abuse and addictions in the developing world.

Bibliography

Anstie, F. E. (1865). The definition of narcosis. In F. E. Anstie, Stimulants and narcotics: Their mutual relations; with special researches on the action of alcohol, aether, and chloroform on the vital organism (pp. 152–169). Lindsay and Blakiston. https://doi.org/10.1037/12215-004. Accessed 17 Mar 2025.

Bhaskar, et al. “The Economic Functioning of Online Drugs Markets.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, vol. 159, July 2019. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167268117302007 Accessed 17 Mar 2025

Central Government. “THE NARCOTIC DRUGS AND PSYCHOTROPIC SUBSTANCES, ACT, 1985.” CHAPTER I, 1985, www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/18974/1/narcotic-drugs-and-psychotropic-substances-act-1985.pdf. Accessed 3 Mar 2025

“Challenges to India’s National Security: The Illicit Flow of Drugs From Myanmar to India-Pre and Post Myanmar Coup of 2021 – CENJOWS,” June 8, 2023. https://cenjows.in/challenges-to-indias-national-security-the-illicit-flow-of-drugs-from-myanmar-to-india-pre-and-post-myanmar-coup-of-2021/. Accessed 11 Mar 2025.

Hayes, Christal. Trump Pardons Silk Road Creator Ross Ulbricht. 22 Jan. 2025, www.bbc.com/news/articles/cz7e0jve875o. Accessed 17 Mar 2025.

“Myanmar Opium Survey 2022: Cultivation, Production, and Implications.” UNODOC Regional Office for Southeast Asia and Pacific, UNODOC, 2022, www.unodc.org/roseap/myanmar/2023/01/myanmar-opium-survey-report/story.html. Accessed 23 Mar. 2025.

“Indicator Group Details,” n.d. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/indicator-groups/indicator-group-details/GHO/sdg-target-3.5-substance-abuse. Accessed 12 Mar 2025.

Jain, Bharti. “Days After Biren’s Resignation, President’s Rule Imposed in Manipur.” The Times of India, February 14, 2025. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/days-after-birens-resignation-prez-rule-imposed-in-manipur/articleshow/118230157.cms. Accessed 14 Mar 2025.

McCann, Conor. “Myanmar Supplies Most of Australia’s Drugs, but Can a New Coffee Culture Help Kick the Habit?” ABC News, February 12, 2024. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-02-11/myanmar-opium-production-and-coffee/103365256 Accessed 12 Mar 2025.

“National_Policy_on_NDPS_published.Pdf,” https://narcoticsindia.nic.in/Notifications/National_Policy_on_NDPS_published.pdf. Accessed 13 Mar 2025.

“NCB Annual Report 2023,” National Narcotics Coordination Portal (NCORD) (Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2001), https://narcoordindia.gov.in/narcoordindia/periodicals.php. Accessed 10 Mar 2025.

Trevino, Steve. “Natural Vs. Synthetic Drugs: The Myth and Reality.” More Than Rehab, 24 Oct. 2024, morethanrehab.com/2023/12/21/natural-vs-synthetic-drugs-the-myth-and-reality/#:~:text=Natural%20Drugs%20are%20Always%20Safer,reactions%2C%20toxicity%2C%20and%20dependency Accessed 12 Mar 2025.

Parth Kumar Chaudhary, Vasudev A Chate, and Shreevathsa, “Insight Into Kautilya Arthashastra With Perspective of Ayurveda”, RGUHS Journal of Ayush Sciences 9, no. 1 (January 1, 2022), https://doi.org/10.26463/rjas.9_1_5. Accessed 17 Mar 2025.

Pti. “Delhi: Dark Web Drug Cartel Busted, Hydroponic Weed Worth ₹2.1 Crore Seized.” The Hindu, January 19, 2025. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Delhi/delhi-dark-web-drug-cartel-busted-hydroponic-weed-worth-21-crore-seized/article69115934.ece. Accessed 15 Mar 2025.

Sudan, Harjeev Kour, Andy Man Yeung Tai, Jane Kim, and Reinhard Michael Krausz. “Decrypting the Cryptomarkets: Trends Over a Decade of the Dark Web Drug Trade.” Drug Science Policy and Law 9 (January 1, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1177/20503245231215668. Accessed 14 Mar 2025.

Transnational Institute, “Poppy Farmers Under Pressure,” report, Transnational Institute, December 2021, https://www.tni.org/en/myanmar-in-focus. Transnational Institute, “Poppy Farmers Under Pressure,” report, Transnational Institute, December 2021, https://www.tni.org/en/myanmar-in-focus. Accessed 10 Mar 2025.

United Nations: UNODC Regional Office for Southeast Asia and the Pacific. “UNODC Report: Record Amount of Methamphetamine Seized in East and Southeast Asia as Synthetic Drug Market Expands and Evolves,” n.d. https://www.unodc.org/roseap/en/2024/05/regional-synthetic-drugs-report-launch/story.html. Accessed 12 Mar 2025.

About the Author

Akash Namboodiripad is a first-year Master’s in Public Policy student. His current interests revolve around History, National Security, Foreign and Tech Policy and its intersections with Political Philosophy and Epistemology. He is an avid reader and enjoys writing on varied topics.