The cost of silence: How institutions escape blame by rebranding suicides as sacrifice

March 11, 2025 2025-03-27 4:50The cost of silence: How institutions escape blame by rebranding suicides as sacrifice

The cost of silence: How institutions escape blame by rebranding suicides as sacrifice

By – Deeksha Gupta and Harsha Grover

Suicide is a phenomenon that affects individuals at every stage of life. People of all age group face different challenges and situations in life which may lead to suicidal thoughts at some point of time in their life. More than 720,000 people die every year due to suicide and it was the third leading cause of death among 15–29-year-olds in 2021 globally (WHO). Suicide showcases deeper institutional, systemic and socio-economic gaps. The recent (February 2025) tragic instances of suicide of young students at Ashoka University and KIIT University have reignited conversations around mental health issues among the youth of India. These instances are often associated with personal distress and psychological factors.

Durkheim argued that suicide is not merely an individual act, but it is a social phenomenon. He referred to it as a social fact. (Social facts are social structures and cultural norms that are external to and independent of individuals, yet constraint their actions).

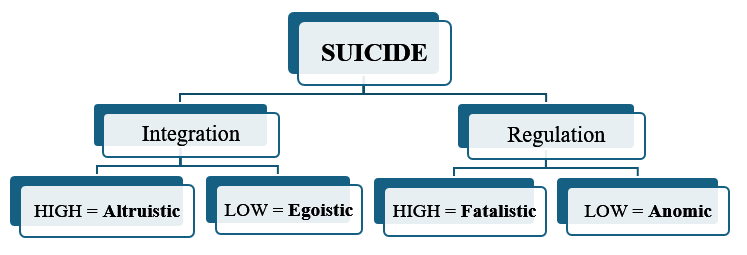

In his seminal work, Suicide (1897), Durkheim defined suicide as “any death caused directly or indirectly by a positive or negative action of the victim himself, which he knows will produce this result.” Durkheim challenged the traditional psychological view of suicide and shifted the focus to its sociological roots, highlighting the influence of social structures and establishing suicide as a subject of sociological study. He also introduced the concept of suicidogenic forces, which he says operates through two fundamental ways: Integration (the extent to which individuals feel connected to society) and Regulation (the degree of control society exerts over individuals).

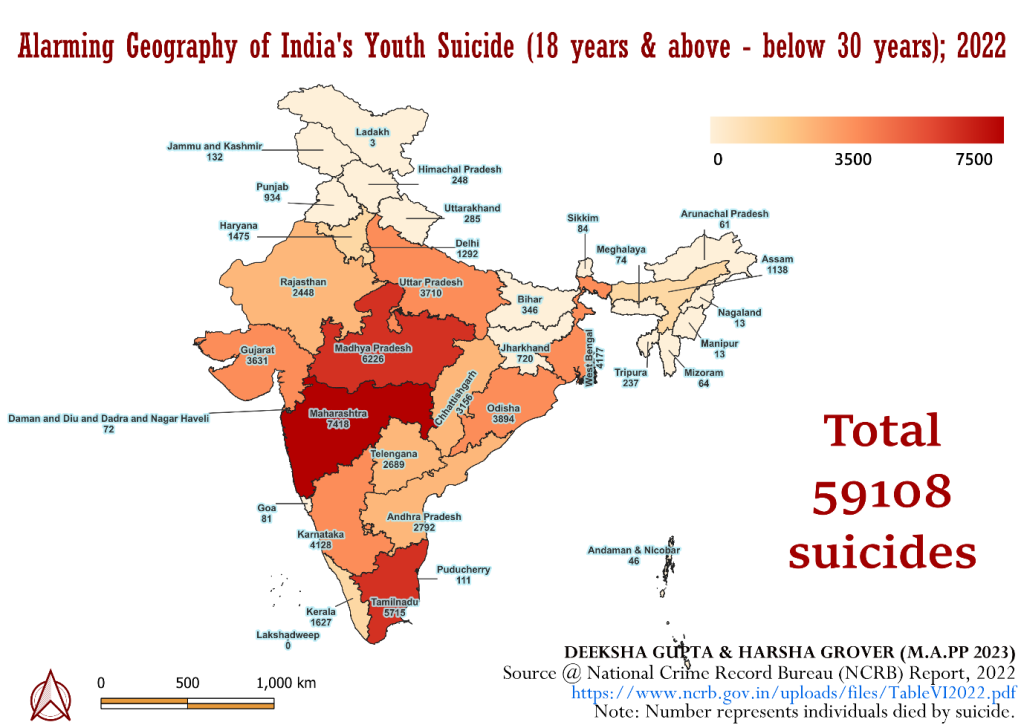

The map reflects an alarming image of youth suicides (age 18- 30 years) for the year 2022. As per NCRB report, 2022, a total of 59108 cases were reported in India (These numbers would be more, taking into consideration the under-reporting (Arya V, et.al 2020)). Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh & Tamil Nadu being the highest recorders showing severe mental health and socio-economic crises. Central and southern India display high prevalence of disparities which leads to stressors like unemployment, academic pressure, financial crises and alienation. The above map is not just a representation of mere statistics, it goes beyond it and presents a heartbreaking reality where each number reflects a life lost, a dream unfulfilled and a family shattered. This is much more than a statistic, it is a predicament demanding immediate action, greater awareness and a more empathetic society.

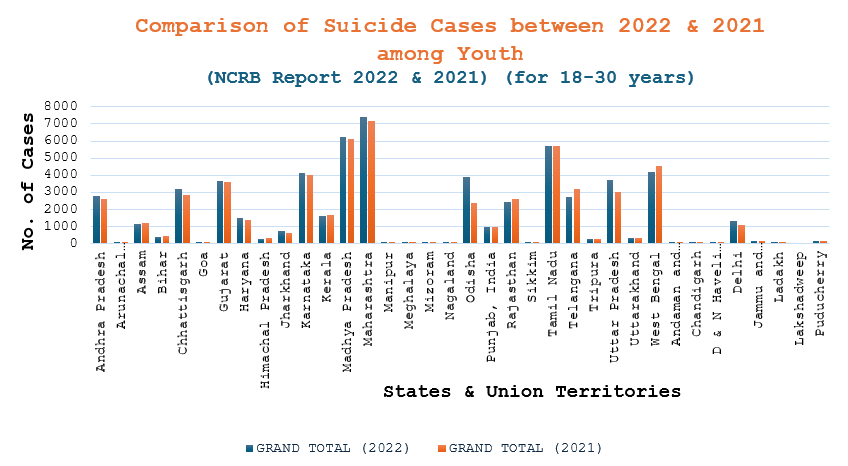

The graph above shows the pattern change for the years 2021 and 2022 of all the states and union territories. As per NCRB reports of 2021 and 2022, The total suicide cases of youth (18-30 years) increased from 56,543 to 59,108 showcasing an overall increase of 4.6% from 2021 to 2022. Five states nearly account for half of all the cases: Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, and Karnataka. Maharashtra alone consists of almost 12.5% of national cases, an increase of over 3.3% year-on-year, followed by Tamil Nadu at 9.7% of national cases. Many states remained relatively stable with numbers, with fewer states like Lakshadweep reported zero cases in both the years. The report reflects regional disparities, where some states experiencing minimal change while the others show alarming increases. Possible reasons for these trends can be social isolation, regional differences in reporting methods, agricultural crises in certain states, rapid urbanization and unemployment in industrialized states.

High degree of integration leads to altruistic suicide. In this situation, individuals sacrifice their life for the greater good of the society. The cases of self-immolation by protestors or young soldiers sacrificing their life to protect the honour of the country.

Low or no degree of integration reflects egoistic suicide. Here, individual feel alienated from the society due to weak social bonds. Case of Ashoka University’s 21-year-old B.A. Political Science student (2025), who committed suicide by jumping from the 10th floor of the hostel building (saying “no-one responsible for his death” in the suicide note) is an example. Students facing intense academic stress without strong social networks are vulnerable to egoistic suicide.

On the same lines, high degree of regulation leads to fatalistic suicide, where individuals feel trapped or under the surveillance by the environment they live in and think it is their fate that they should commit suicide to end the oppression. Saurabh Kumar Laddha case (2024), he was a consultant at McKinsey & Company in Mumbai, at the young age of 25 he died by suicide by jumping from the apartment building. Reports suggest that intense work pressure played a huge role in this act. This shows the other side of the companies/organisations which create high pressure work environment for the individuals without any acknowledgement of the mental health of the employees.

Lastly, the condition of low degree of regulation, which leads to anomic suicide. Individuals feel lack of guidance, uncertainty and hopelessness in the society they live in, it occurs when traditional norms in the society cave in. It often occurs in the period of financial crises, economic recessions & societal instability. The tragic case of 26-year-old farmer in Tamil Nadu, who committed suicide by consuming poison because he could not repay the loan taken for buying a tractor, is an example of the same.

In our opinion, Egoistic and Anomic suicide which stem from isolation and societal instability respectively are mostly acknowledged as personal tragedies, however, there is a noticeable hesitation in accepting Fatalistic suicide because of excessive regulation/control. Instead, more than often these cases are reframed as Altruistic suicides, portraying the victim as a Martyr or a self-sacrificing individual who is tired of fighting the socially oppressive structures.

The case of Rohith Vemula (2016) is a great example of how Fatalistic suicide is often rebranded as Altruistic suicide, allowing the society to conceal uncomfortable truths. Vemula, was a Dalit PhD scholar at the University of Hyderabad, who faced institutional caste discrimination, academic suspension and financial instability, which left him with no control over his future. This is a classic case of fatalistic suicide, where the oppressive structure leaves an individual feeling completely trapped. However, in the aftermath of his death, his suicide was branded into a symbol of resistance and was perceived as an act of sacrifice for social justice, which basically is an altruistic branding. Though this mobilisation was crucial for discussion regarding caste-based discrimination, but it also shifted the focus away from the systemic failures that pushed him to such despair in the first place.

Similarly, the suicide case of EY employee Anna Sebastian Perayil shows the same pattern of fatalistic suicide being rebranded as altruistic. Perayil, allegedly faced immense corporate pressure, unrealistic work expectations and an overall toxic work culture which left her feeling trapped, all of this being the hallmark of fatalistic suicide. However, post her death the focus quickly shifted to her resilience, dedication and a broader discourse on corporate burnouts. Much like Vemula’s case, her suicide became a symbol of workplace stress, toxic corporate culture and mental health advocacy, but this altruistic rebranding conveniently diverted the attention from the harsh realities of exploitative corporate culture.

While institutions generally evade responsibility and accountability by reframing fatalistic suicide as acts of self-sacrifice, there are exceptions where the institutions have acknowledged systemic failures, and it has led to some meaningful changes. The tragic suicide of S. Anitha (2017), a Dalit girl who died from suicide after being unable to secure a seat in medical college due to imposition of NEET, despite scoring high marks in her state board examinations. Her death highlighted the disadvantages faced by the marginalized communities. This instance led to a public outcry and the Tamil Nadu Government introduced a 7.5% reservation for government school students in medical admissions and continued the push for removal of NEET for the state. The above case highlights that when the institutions recognize their own systemic failures, change however slow becomes possible. However, for a long term and everlasting impact, such recognition by institutions cannot be an exception and must become the norm.

The trend of rebranding fatalistic suicides as altruistic not only misrepresents the reality but it also leads to a dangerous trend of justification of suicide itself as if these individuals committed suicide for a greater cause. By portraying their death as an act of sacrifice rather than a result of systemic oppression, institutions as well as society avoid taking responsibility. Instead of confronting the exploitative academic, corporate and social structures that makes an individual feel trapped and suffocated, we turn their suicide into a symbol of resistance, mourning them while continuing to uphold the very system that broke them.

These instances of suicide though spark debates but it rarely leads to any meaningful institutional change. The institutions like universities continue to be hostile to students from the marginalised communities, workplaces continue to demand unsustainable productivity and social hierarchy continue remains unchallenged. In the end by romanticising these tragedies instead of addressing the deep-rooted systems that cause them, we create a vicious cycle where nothing really changes, making the next loss not a question of if, but when.