“Supreme Court Questions NCPCR’s Approach to Madarsa Education, Seeks Even-Handed Treatment Across Religious Institutions.”

October 22, 2024 2025-03-01 23:57“Supreme Court Questions NCPCR’s Approach to Madarsa Education, Seeks Even-Handed Treatment Across Religious Institutions.”

“Supreme Court Questions NCPCR’s Approach to Madarsa Education, Seeks Even-Handed Treatment Across Religious Institutions.”

By Niyati Dhiman

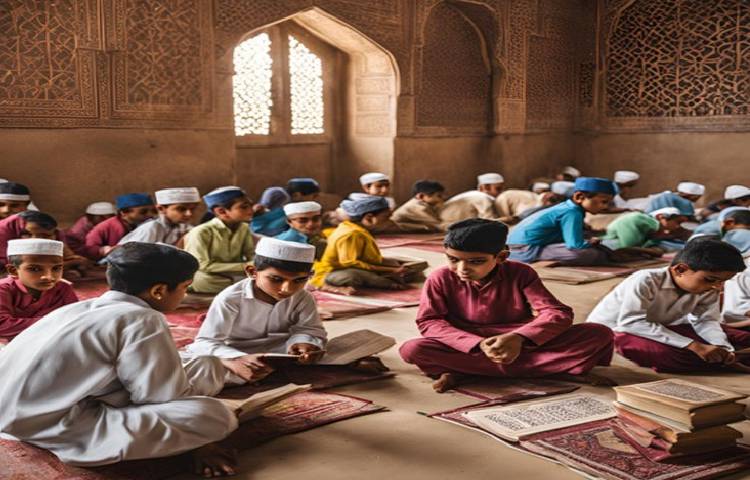

In a significant hearing on October 22, the Supreme Court examined the stance of the National Commission for the Protection of Children’s Rights (NCPCR) regarding the Madarsa education system in India. The Commission had raised concerns about the Madarsa system’s compliance with the Right to Education Act (RTE), particularly with regard to the lack of secular education. The case, involving appeals against the Allahabad High Court’s decision that declared the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004, unconstitutional, has drawn considerable attention to the issue of religious education versus secular schooling in India.

During the hearing, the Court questioned the NCPCR about its selective focus on Madarsas, asking whether it had adopted the same approach toward similar institutions in other religious communities. Justices DY Chandrachud, JB Pardiwala, and Manoj Misra raised concerns about whether the Commission was treating all religious institutions equally. Specifically, the Court inquired if the NCPCR had issued directives regarding religious education in institutions of other religions, such as monasteries and gurukuls, where children also receive religious training. The Court questioned why the NCPCR appeared to be singling out Madarsas, particularly when similar systems exist in other religious contexts.

Justice Pardiwala, in particular, asked whether the NCPCR had conducted an in-depth study of the Madarsa syllabus and understood the difference between ‘religious instruction’ and ‘religious education.’ He stressed that religious instruction, as per Article 28 of the Constitution, was distinct from religious education, and the latter should not be conflated with the medium of instruction in schools. He also noted that the teaching of religion was not prohibited, as long as it was not substituted for secular education.

Chief Justice Chandrachud further questioned whether the NCPCR’s objections were based on the idea that children should not undergo religious instruction at all, especially when similar instruction was provided in other religious institutions across the country. The Court also asked if the NCPCR had issued any guidelines to ensure that children attending such institutions also received secular education, such as subjects like science and mathematics.

NCPCR counsel Swarupama Chaturvedi clarified that the Commission was not against religious instruction but was concerned about religious studies being seen as a replacement for compulsory secular education under Article 21A of the Constitution. She emphasized that children must not be deprived of their fundamental right to education, which should not be substituted with religious instruction alone. Chaturvedi also stated that the NCPCR had sent repeated reminders to state governments regarding the need for free and compulsory education for all children.

In response, the Chief Justice pointed out that the NCPCR’s focus appeared disproportionately on Madarsas. He asked for clarification on whether the Commission had issued similar instructions regarding religious institutions in other communities. The Court’s inquiry aimed to determine whether the NCPCR was being even-handed in its treatment of all religious educational institutions across India. Chaturvedi agreed to seek further instructions from the Commission and file an additional statement on the matter.

The hearing also included arguments from Senior Advocate MR Shamshad, representing the petitioners, who criticized the NCPCR’s stance as Islamophobic. He argued that the Commission’s report, which had been widely circulated in the media, created a negative perception of Madarsas. He further suggested that if the state provided more general schools in Muslim-majority areas, the Madarsas would naturally decline.

The case raises crucial questions about the balance between religious education and the right to secular education in India. The Supreme Court’s decision will likely have significant implications for the future of religious schools and the interpretation of children’s rights to education under the Constitution.

Case Title: Anjum Kadari and Ors. Vs. Union of India (UOI) and Ors., Supreme Court

Citation: 2024 INSC 831